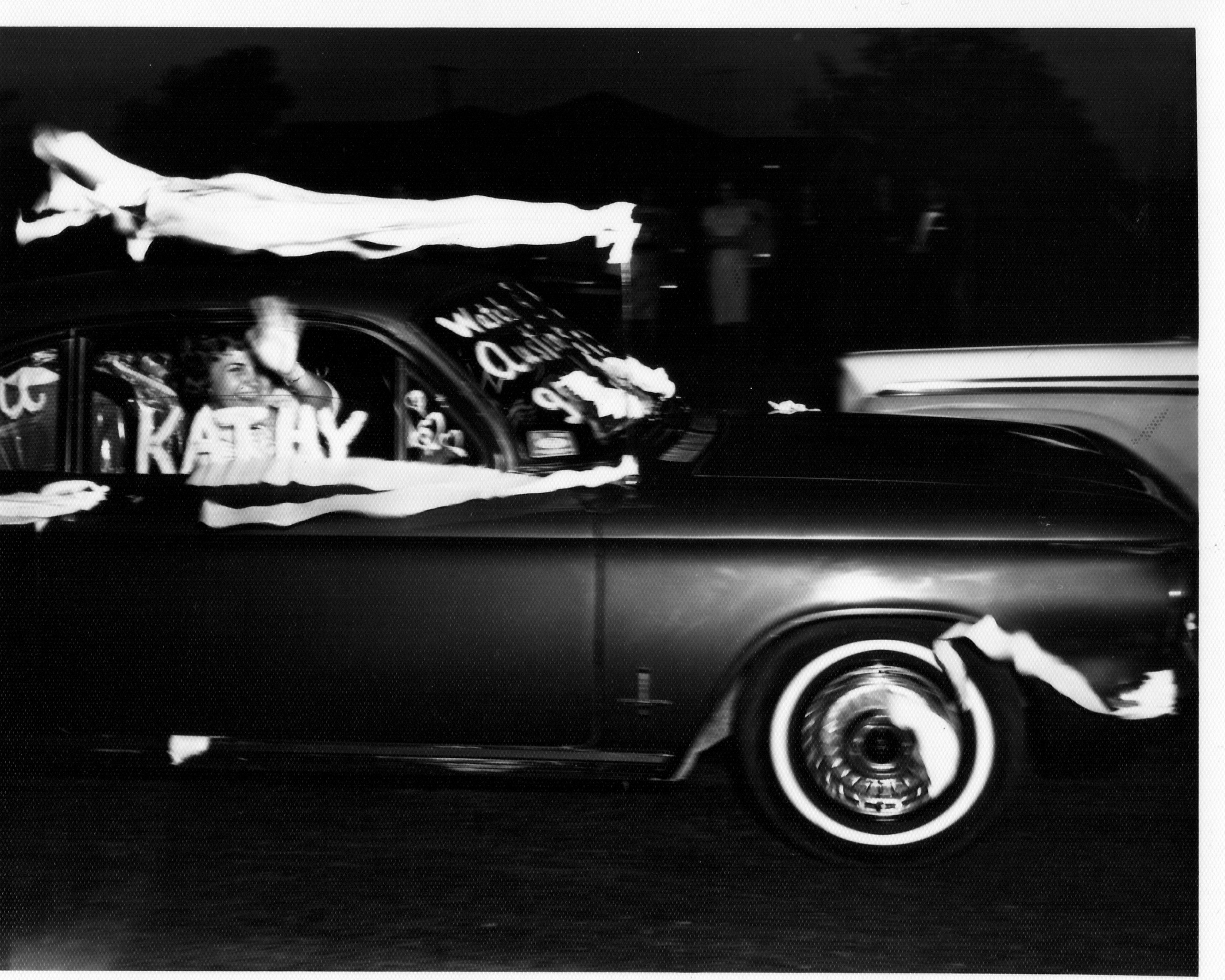

Kathy Leissner on her wedding day, waves goodbye to family and friends (17 August 1962) courtesy of Nelson Leissner

In May, my “A Side” playlist for MASS: A Sniper, a Father, and a Priest was published at Largehearted Boy (many thanks, David Gutowski!).

Most people do not realize that by the time he took his position at the UT Austin tower on August 1, 1966, to kill 15 and wound 31, sniper Charles Whitman had already brutally ended two lives in private: his mother, Margaret’s, and his wife, Kathy’s. Both women were looking for transformation in their lives. As research now shows us, it’s all too common for public violence to be preceded by violence at home.

MASS tells the story of a guy’s world–in families, in churches, in the military, in larger society–where women were too-easily erased, often violently, to serve the purposes of men. Despite five decades of social change, marriage or intimate partnership still remains a death sentence for far too many women.

I wanted the “B Side” for my book to include women’s voices only. We need to imagine, and create, a world where it is no longer a default expectation for women to suffer and be sacrificed as “solutions” for personal, social, or theological problems. We need to adjust our volume so that women can be heard about their experiences and desires, about what they witness and know, long before (and whether or not) any gun goes off in public.

Our use of the word “victim” often reduces and erases the complex humanity of individual lives. Kathy Leissner Whitman was a woman well-loved by family and friends, a new college graduate and a science teacher. Her husband cut short her life, and the future she was living towards, two weeks after her 23rd birthday, and two weeks before the fifth anniversary of her marriage. It is past time for Kathy, for all women, to be heard and respected on their own terms. #metoo is not just a moment; it’s the work of generations.

Here is my “B” list: #rightsideup #eccefemina

Moon River—Audrey Hepburn #notSinatra There’s one moment I love in the film version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (sigh…yes, I know it’s a movie with sooooo many problems…). Holly Golightly, played by Hepburn, perches in the windowsill above her fire escape, hair tied back in a towel, grey sweatshirt and jeans, strumming her guitar and singing. The sound of her voice draws the white, blonde, writer guy (George Peppard) away from the typewriter with desk and floor littered by crumpled failures and to his own window. It’s a moment that passes quickly into the rest of the movie. But there’s hope planted there for a significant starting place: that a dude could attend to a woman’s voice and be more than charmed. Maybe he can learn something without being existentially threatened, without dismissing or mansplaining back to her, without doing much worse.

Were You There?—Mahalia Jackson Jackson’s voice poses the excruciating question over a cascading piano: “Were you there …. when they crucified my Lord?” It’s an African American woman who calls us to account as she traces an injustice, a torture (“when they nailed him to the tree?” “when they laid him in the tomb?”), building to the same conclusion at the end of each verse: “Sometime it causes me to tremble… tremble… tremble….” So were we part of the cruelty? Did we turn away? Jackson doesn’t let us off the hook. She wants us to join with her in remembrance, to witness alongside her–not only the awful spectacle, but our own role.

I Say a Little Prayer—Aretha Franklin I love this gentle, matter-of-fact valentine from the Queen of Soul (RIP), a cover of Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s tune for Dionne Warwick. It’s devotional without evangelizing too hard, even with its plea at the very end to “answer [her] prayer” for reciprocity. After all, isn’t that what she deserves? But love is only part of the speaker’s life, not the whole of it. She puts on her makeup, she picks out a dress, she runs for the bus, she has a coffee break. In all those simple activities she is connected to her beloved: “Darling believe me, for me there is no one but you. Please love me too. Answer my prayer.” This woman has work to do, bills to pay, a self to care for on-the-daily. There is no wounded lover here. She can love and live at the same time.

Zombie—The Cranberries This song tears at my insides every time, but I always turn it up. Delores O’Riordan’s voice testifies to the impact of religious violence in Northern Ireland, specifically a Belfast bombing in 1993 that killed two boys. At so many turns in MASS, there were women and family members nearby—as bystanders or targets—when adult men turned on their rage with belts, fists, guns, and shame. Almost always, the violence was followed by coldness, indifference, or outright denial of the damage left behind: “With their tanks and their bombs/ And their bombs and their guns./In your head in your head they are crying/ In your head/ In your head.” This song forces us through the numbing effects of war zones or abuse at home, in the streets, or in church, even as the mental movie plays itself out over again and again.

It Ain’t Me, Babe—Joan Baez #notDylan I’ve only seen one live recording of Baez’s version from 1965. “I guess,” Baez said, introducing the song, “I’m anti-marriage.” But her rendering is even more complex than that. To hear “It ain’t me” in the serene, clarion voice of Baez offers a beautiful contradiction to the song as sung by Bob Dylan, who seems to be rejecting the clingy, “scorned” woman. Baez lets us hear from a voice who is countering an assumption about herself, who understands her own value and power. I see this song as turning point in this set, the dawning of a realization that can be literally, physically dangerous in unhealthy relationships: when one partner realizes that it’s better–often safer–to be alone than to stay attached.

Dog Days Are Over—Florence and the Machine The power of “Dog Days” sneaks up over the bright ukelele chords every time, and the tempo changes pull back and forward across the contradictory turns of thought. How could happiness turn bad? Anyone who’s been in a toxic affair knows all too well—“like a bullet in the back/struck from a great height/by someone who should know better than that.” When the reality hits, the urgency is often very loud, or worse. According to the Domestic Violence Hotline, it takes a person up to 7 times to leave a coercive or violent relationship before leaving finally, for good. This feels like the anthem for the final time that person races across the invisible line after so many tries. I imagine an alternative reality for Kathy Leissner when I hear this song. I picture her packing one bag and tossing it into her car, taking the dog Scocie, and driving away from Austin and Charles Whitman, never looking back, and never needing to look over her shoulder.

It’s A Fire—Portishead This song pairs with “Dog Days” because it’s the quieter, I-didn’t-quite-make-it-out-yet voice settling into the reality that all is not so well and that there will be a next, awful time. “This salvation I desire/ keeps getting me down.” The voice here is the spirit longing for an exit, waiting to decide, in a real world where on-the-ground conditions can work against our own best judgment, social intelligence, and instincts for survival. Struggling to breathe “through this mask,” Beth Gibbons sings quietly for the step-by-step surviving: “So breathe on, little sister, breathe on.“

I Will Survive—Gloria Gaynor This song is not only a woman’s anthem but an LGBTQ one: a survivor’s song, in full-throated force, tracing its complete awareness of why the toxic relationship must end. Insecurity and fear transform into clarity and personal power. Gaynor’s voice isn’t buying the manipulations, the shame or guilt, anymore. “That sad look” on her lover’s face doesn’t have any power any longer. She is banishing him, banishing all of the bullshit, reclaiming her time, her space, her life: “Go on now, go, walk out the door/Just turn around now/’Cause you’re not welcome anymore.”

Ain’t Got No/I Got Life–Nina Simone In most narratives of mass violence, whether in private or at home, we discover stories of men (often white men) who use violence against others to prove themselves superior when their sense of entitlement is frustrated, to avoid dealing with their own history and their own mess, and when they have accomplished or contributed very little. Miss Simone’s song begins quietly and mournfully from a place where entitlement is not even on the menu, only the unending realities of deprivation and marginalization. She unspools the details mournfully: “I ain’t got no home, ain’t got no shoes/Ain’t got no money, ain’t got no class/Ain’t got no skirts, ain’t got no sweater…/Ain’t got no perfume, ain’t got no bed/…Ain’t got no god.” In the face of all this–in a world where domination and suppression is part of a social order–Miss Simone’s voice gets louder, rising with full-throated indignation: “Hey, what have I got?/ Why am I alive, anyway?/ Yeah, what have I got/Nobody can take away?” In sudden tempo change, she launches into litany of appreciation to her own body, part by part: “Got my hair, got my head/Got my brains, got my ears/

Got my eyes, got my nose/Got my mouth, I got my smile…./I got life.” This is not a denial of the grim realities; it is a blessing for the self, where coercion has no place. I believe this is one of the most beautiful pro-Black, pro-woman, and truly “pro life” songs ever recorded. Nina Simone, “the High Priestess of Soul,” gets the last word.

Recent Comments