opening the USCCB General Assembly in November 2018 (photo: Jo Scott-Coe)

This week, the US Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) gathers in Baltimore for their spring assembly. Last November, though I was not granted credentials, I attended as an external witness and listener for local (and traveling) activists and survivors. The men in charge sequestered themselves in the hotel, tensely bubble-wrapped away from the general public they have wounded.

This round, the gathering falls approximately one week after Nicole Winfield of the Associated Press broke the story of public allegations by a married woman, Laura Pontikes, who alleges she was manipulated for sex during “counseling” sessions by Msgr. Frank Rossi, former Chancellor in the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston. The official who handled the woman’s original complaint two years ago was Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, Archbishop of the diocese and now President of the USCCB.

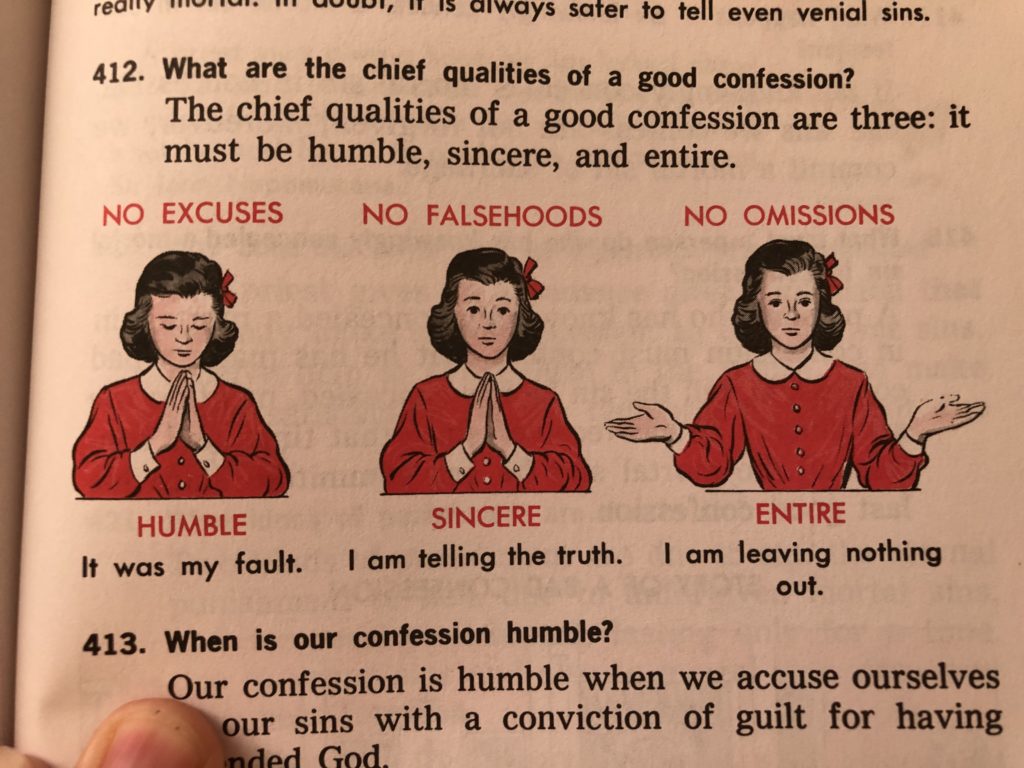

Rossi is alleged to have committed a canonical crime as well: absolving someone he had preyed upon when she confessed “the affair” to him as her sin. Self-blame and hyper-responsibility are not uncommon with religious victims, often viewed within the language of their traditions as “accomplices” in their own abuse, despite the actual power disparities that undermine mutuality and consent.

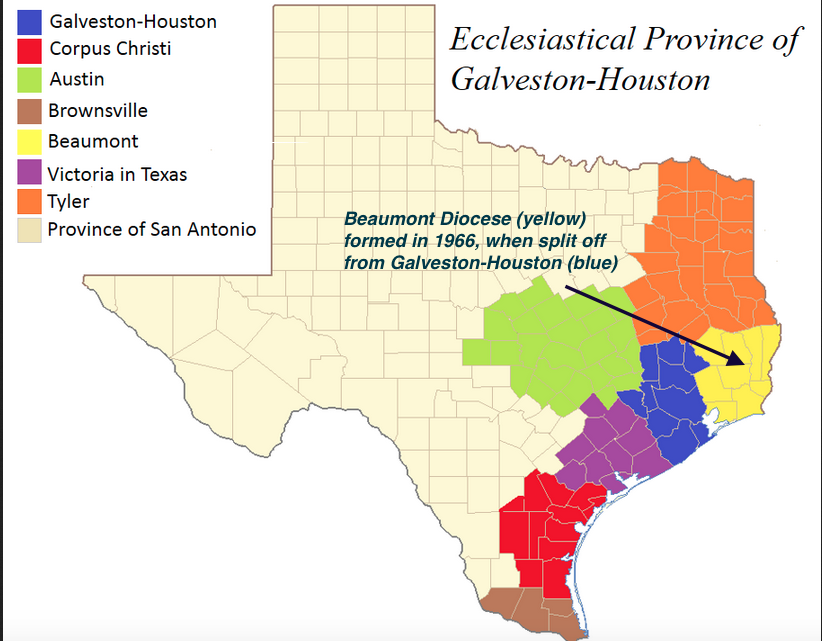

Finally, Pontikes alleges now that despite assurance that he would remove Rossi, DiNardo merely relocated the well-connected priest, after receiving “treatment,” to a parish two hours east of central Houston, in the Diocese of Beaumont.

The Rossi case may well become a Rosetta Stone for power, privilege, and secrecy in Houston since 1970

Pontikes’s story matters because it shouldn’t have happened (even though we know it has, and does, again and again). It also matters in a specific environment to call out Rossi, a high-level broker of institutional memory and power in ADGH.

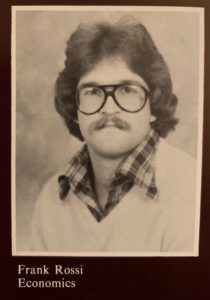

University of St. Thomas 1979. Courtesy Siobhan Fleming, PhD Personal Collection

In 1975, Rossi graduated from high school in Alvin, TX, and went on to graduate from the University of St. Thomas in 1979. He studied in Rome and was ordained for Galveston-Houston in 1983.

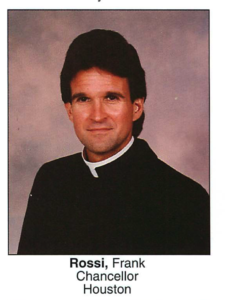

Within only 3 years of ordination, in 1986, Rossi was already Vice-Chancellor to Bishop Joseph Fiorenza, the newly appointed Bishop of Galveston-Houston. Fiorenza had been ordained in 1954 and spent the 1970s as Vice-Chancellor, then Chancellor, of ADGH, then briefly Bishop of San Angelo.

As Fiorenza’s Chancellor, Rossi was a man who would have been ecclesiastically connected by paper and privilege to many settlements of complaints made by Catholics in the diocese. If any priest names are missing from the Jan 31 list of “credibly accused” priests for ADGH, the odds are high that Rossi would know who they are (or were), and what happened to their cases.

Laura Pontikes’s Case and the Proud, Awful, Very Catholic Bro Tradition: Ignore and Blame Women

Laura Pontikes came forward to stand up about Rossi’s manipulation and abuse as an adult woman who is also white and who still identifies as faithfully Catholic. In addition, she is married, affluent, and locally connected. Yet it was not local media or local activists who broke the story. Counter-intuitive as it may seem, even the most privileged victims in insular hometown environments may need to go outside the immediate system in order to be seen and heard for an impact.

Stereotypes of victims who “count” in the abuse conversation emerge from the commonly mistaken belief that only children, especially heterosexual boys, matter as the most legitimate or serious victims. Much of the American panic about sexual abuse draws from an ugly and inaccurate conflation of pedophilia and homosexuality, a stew of official Church teaching about homosexuality (as a “disordered” identity), broader patterns of homophobia, and mistrust of women’s sexuality, bodily autonomy, and personal authority.

Catholic women and girls are taught, at a muscle-memory level, how their bodies are always the territory of male doctrines, opinions, and aesthetic fantasies that originate in Western European ideals. Women’s “weakness” is assumed as default by the very authorities who judge and blame for any and all perceived impurities and expected flaws. And yet–in the most effective gaslighting technique ever–there are statues and icons of women’s bodies on display everywhere.

The laughable flaw of this horrible setup is its fundamental underestimation of women’s real ability to see and understand what’s going on within realities of their own complicated daily experience. But the trouble is where to go and who to talk to when when the light goes on. Whatever one’s relationship to the church, there is a magic when women can hear each other and move forward into truth, blasting through the smilingly misogynist, homophobic, and racist “bro” templates that keep righteously pressing the mute button.

There are records of these awarenesses. For a classic, read “Hombres necios que acusáis” by Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a brilliant writer and 17th century nun in Mexico who had her own very public and doomed conflict with a bishop. Despite her achievements and due to her commitment to helping her sisters, Sor Juana died of plague, and (no shock here) will never be canonized as a saint. She doesn’t need to be a saint to matter.

Documentation that reveals where the shushing happens tends to turn scrutiny back where it belongs: towards the institutional structures inside specific communities. The Keepers in 2017 demonstrated (among many horrors) how suspected priest abusers of young men in Baltimore were moved to all-girls’ school as a “solution” for the problem of their predatory behavior. A white nun and teacher, Kathy Cesnik, who got wind of the abuse also “got pregnant,” likely confided in a priest, and ended up dead in 1969. Her death was a cold case until her former girl students, now fully grown, some of them abuse survivors themselves, started asking questions.

In 2018, a documentary revealed how Jesuits hid predatory priests who preyed upon indigenous Alaskans while “ministering” to them. One priest had twenty known women and girl victims, with the youngest just 6 years old. Seven years earlier, in 2011, a documentary on PBS Frontline traced abuse of Alaska natives in the small village of St. Michael. As recently as 2018, under “progressive” Pope Francis, the Catholic Church has refused to apologize for generations of indigenous abuse. We could go back through Catholic empire forever.

And what else about Texas? Consider one powerful story of horrific context: the assault and murder of Irene Garza by a priest in 1960, in the border town of McAllen TX. A crime not adjudicated until 2017. Picture it: In 1960, a Latina girl who wanted sanctuary at church went to confession with a white priest, and she never came back. Fifty-seven years ago. Fifty seven years for her family to see any hint of justice.

(Jo Scott-Coe, personal archive)

Pontikes’s complaint may bring a history of raided records, and diocesan boundaries, into focus.

The white bros always show who really matters to them. Women across a spectrum of identities use church networks for safety and connection. But all too often assumed sanctuaries repeat broader structures of pervasive dehumanization. In still-segregated faith communities, women’s service is always demanded and expected. Some women are seen while others are rendered invisible, elbowed aside for other women scratching for validation in a doomed hierarchy. Poison for all.

In the same families where men’s pain and victimhood may be admitted as tragic or disgraceful, women’s abuse may be accepted or normalized. This disorientation creates environments where abusers, and their handlers, have prevailed.

It can take generations for women across boundaries of time and space to reconcile their precious–or rejected–faith traditions and family experiences with their own need, and right, to speak out.

Bishops have been dividing the faithful for decades. That time is up.

The Diocese of Beaumont takes its name from the town where Joseph Fiorenza himself grew up, a smaller diocese created in 1966 when it was split off from Galveston-Houston. The Diocese of Beaumont now stretches geographically along the gulf near Baytown to the Texas-Louisiana border. Rossi is one visible example of Galveston-Houston “relocating” one of its own problems. But in the religious history of Catholic Houston, Beaumont is not far away at all.

Rossi may also be the youngest living official link between the institutional memory of two bishops: retired Archbishop Joseph Fiorenza and Cardinal Daniel DiNardo. People forget, or do not know, that Fiorenza was also “top dog” in the USCCB: Vice-President (1995-98) and then President (1998-2001), just before the Boston scandal broke in 2002.

The Rossi case will draw attention to the relationship between Galveston-Houston and Beaumont. To what extent did ADGH use Beaumont as a landing ground for predators and other problems? Consider the case of Henry A. Drouihlet, named by Beaumont (but not Houston) as “credibly accused” of abuse, a priest who spent the first thirty eight years of his priesthood inside ADGH, including two decades as Diocesan Director of Catholic Scouting.

It has been seven months since authorities raided the Houston chancery, the same month bishops last gathered for their last (distastrous) meeting in Baltimore. Pontikes’s complaint returns us again to the question of records, and the Jan. 31 list.

The Rossi story matters, and it is also the key to broader knowledge. How might the house of Houston’s cards begin to fall in on themselves, yielding more information for survivors and victims, and for the general public trust?

Time’s up for a “humble, sincere, and entire” confession in Houston. The faithful, and the unfaithful, are not waiting patiently anymore. Take a page from the women in your catechism, from all those women you’ve been shaming and ignoring forever.

Time for more brother, less bro.

Recent Comments